Whether you are a bit curious about Semantic Search or not, I’m convinced that the notion of search intent has, at least once, whistled to your ears. Anyone seeking better visibility on Semantic Web needs to understand how search intent works.

If you take a look at the articles mentioning search intent, you quickly realize that this topic is oversimplified and that you can’t fully understand how important it is for information retrieval and SEO. So I want to bring a little more depth to this topic through this article.

It is an understatement to say that knowing what is really behind the search intent will help you better understand the behavior of your audience on the web. As a result, it will give you the opportunity to build a more solid and sustainable semantic framework.

Let’s start with a brief search intent definition.

How can we define search intent ?

In the collective spirit, search intent is defined as the main user’s interest when typing a search query. A very simplistic definition that is often supported by 4 forms of research:

- navigational research

- informational research

- commercial research

- transactional research

But if one seeks to understand the meaning of search intent in a more accurate way it is wiser to first introduce the concept of information need. Before defining what information need means, I suggest to find out what is an information and what is a need. For the first one, I’m going to use the definition given by Serge Cacaly in his book “Dictionnaire encyclopédique de l’information et de la documentation ” published in 1997.

What is an information ?

Serge Cacally defines the word “information” as “the recording of knowledge with the aim of its transmission. This purpose implies that knowledge is inscribed on a support, in order to be preserved, and coded, any representation of reality being by nature symbolic.”

What is a need ?

A need is defined as a feeling that leads living beings to certain acts that are or seem necessary to them.

What is an information need ?

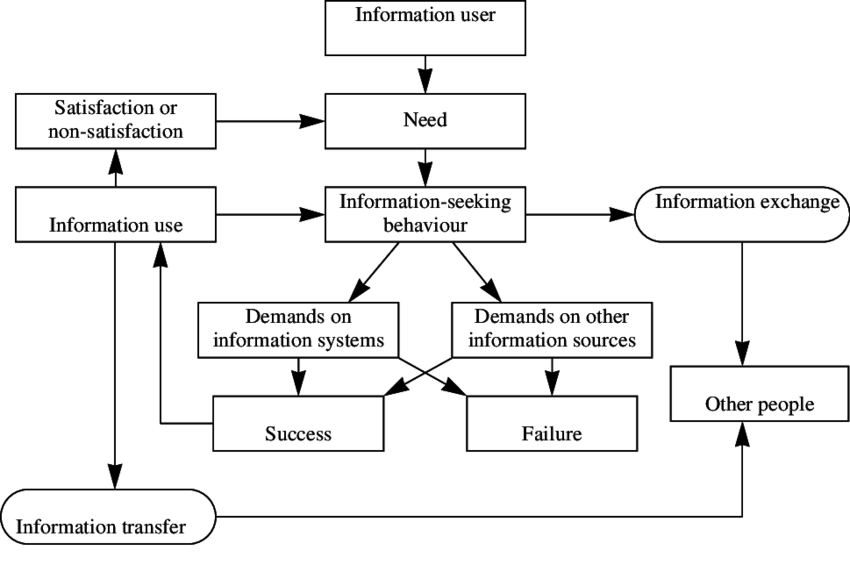

An information need would thus be considered as a feeling, a sensation that would lead the user to engage in an information seeking activity. For Berkin (1980: Anomalous states of knowledge as a basis for information retrieval) and Dervin (1986: Information needs and uses), the need for information is summarized by a person’s awareness of a gap in his or her knowledge. Therefore, it is considered that a person seeking information knows nothing about his need and is therefore not qualified to express it directly.

This representation of the need for information can also be deepened by exploring two opposite environments: the need for information on the Internet and the need for information outside the Internet.

Information need and demand process in a given environment

Need for information outside the web

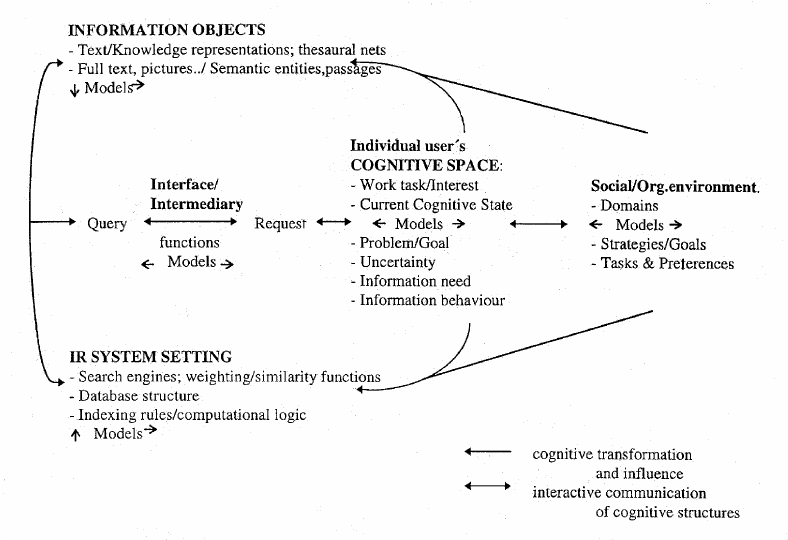

In our daily life, the need for information is only visible from the search activity of the person who becomes aware of his absence or lack of knowledge. In 1992, Peter Ingwersen (Information Retrieval Interaction) used the IR (information retrieval) work of C.J. van Rijsbergen to compare this need for non-tangible information to the dark matter studied in astrophysics.

To clarify, let us imagine that the observable element is the request made by one individual to another. This other individual can be anyone, a friend, a colleague, a cashier. Following this request, a dialogue will arise with the sole aim of refining the need expressed.

Yves Le Coadic (1998: Le besoin d’information. Formulation, negotiation, diagnosis), speaks of this dialogue as being a negotiation phase in which two individuals confront each other in order to match an information need with a collection of knowledge.

Dialogue constructs a negotiation between two people, with the professional having to be aware of the physical, linguistic and cognitive distances that interact.

https://www.persee.fr/doc/reso_0751-7971_1999_num_17_94_2150_t1_0268_0000_1

Information need in SRI

As soon as a person becomes a user of an information retrieval system such as any search engine, his or her information need (remember, information need = search intent) is naturally expressed through a search expression.

This search expression represents very roughly, in most cases, the underlying information need (we come back to our definition from the beginning).

In what I could call “his most famous paper”, Robert Taylor (1968: The process of asking questions) mentioned a “label effect” from which he expressed a tendency for individuals not to express clearly all that they know, but rather to use only a part of their knowledge that is considered sufficient. A notion validated and followed several years later by Peter Ingwersen (1982: Cognitive Information Retrieval).

All this leads us slowly but surely to the representation of the user’s search behavior. Being aware of his lack of knowledge in a domain and that this lack of knowledge results in a very random demand for information, how does the individual undertake his journey towards what will allow him to gain more knowledge and to make his information search process evolve by ricochet effect?

User behavior when searching for information

Human beings will always try to make the least possible effort to get what they want and this rule also applies to information search. Even with a good knowledge of his information need – his search intent – a user will direct his request using few words and/or concepts to define it. This laziness is not unknown in the information retrieval community since many works have already been published on the subject. In this respect, I suggest you the following readings to feed your curiosity:

- Jansen, Spink & Sarasevic (2000): Real life, real users, and real needs: a study and analysis of user queries on the web.

- Ingwersen (2000): User in context.

- Spink (2002): Toward a theoretical framework for information retrieval(IR) evaluation in an information seeking context.

A difficulty of expression that search engines have been able to overcome by offering the user potentially relevant answers in relation to the search expression typed.

We cannot talk about the need for information without talking about the effort that it requires from a user for his search. For an information need to lead to an IR activity, the individual must believe that there is an answer to his question and that the effort required to obtain this answer is not too great compared to the expected gain.

Indeed, users are not always ready to make undue efforts to satisfy their need for information; they must have an interest and be motivated to make the effort.

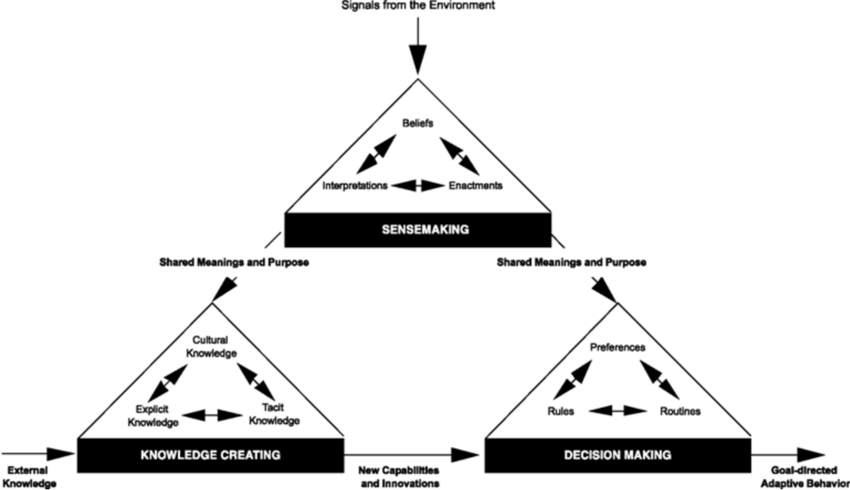

Any search for information requires at least three types of effort (Choo, 2006: The knowing organization: How Organizations Use Information toConstruct Meaning,Create Knowledge,and Make Decisions):

- physical efforts (moving to the source),

- intellectual efforts (learning how to use an IRS, how to consult this or that source, how to link information together, how to reason from it)

- psychological efforts (being ready to consult unpleasant information or sources).

These efforts can be significant for the user who will often have to repeat his request through several search expressions. Depending on the results obtained, the need may then evolve, and lead the user to reconsider it and therefore to search for information differently.

Brenda Dervin has extended this approach in her “meaning construction” model (https://journals.openedition.org/edc/2306) of the need for information, in which she establishes that seeking information is seeking to understand the world around us.

Information need and user uncertainty

Tefko Saracevic (1996) https://scholar.google.com/citations?user=ERzz6cUAAAAJ&hl=en

When a person is aware that he does not know something, that he lacks a piece of data in his knowledge, he unconsciously undergoes a state of uncertainty which will lead him to look for the missing information. This uncertainty can be linked to two things:

- either a problem to be solved (this state is very often put forward when we talk about search intention in Web Semantics)

- or an obvious disparity between what we observe of an event, its characteristics, and what it actually is.

The process of information retrieval by the individual can then be seen as a path to reduce this uncertainty, or even make it disappear. But not everything is done in a snap of the fingers. To go from a state of uncertainty of one’s knowledge to a state of certainty requires a series of steps which form the search for information:

– Identification of the problem

– Definition of the problem

– Solving the problem

– Proposal of a solution

On a more philosophical aspect, Plato was also interested in this paradox in Menon

Quotation : how to look for a thing we don’t know ? Among the things we don’t know, how do we know which one to look for? How can we identify that the information found is the one we are looking for?

To search effectively for information, one needs prior knowledge (Rouet, 2000; Tricot, 2003). One only searches if one knows that one does not know and that one can find. One must accept the uncertainty that results from this and have the motivation to reduce or eliminate it.

What are the different types of information needs?

It might be time to talk about the different information needs as well. As I mentioned in the introduction, most of the time – if not all the time – articles that mention search intent break it down into 4 types of searches:

- a navigational search intent

- an information search intent

- a commercial search intent

- a transactional search intent

We could also go further by highlighting :

- a geographical search intent (local)

- a brand search intent

- a news search intent

In my opinion, and in relation to what has been explained throughout this article, we quickly notice a certain dissonance between what is stated above and repeated by most people and what is actually a need for information. Namely, a feeling of lack (in one’s knowledge) which leads to fill it.

In order to improve the assistance to users of documentation centers or information retrieval systems, different scientists have proposed typologies of information needs

It is Wilson (1981: On user studies and information needs) who has perfectly deciphered this notion of need by comparing it to the primary needs, without which we are nothing.

There is a confusion, perhaps more fundamental, in the association of the words information and need. This association imbues the resulting concept with connotations of a basic need, qualitatively similar to other basic human needs.

https://www.emerald.com/insight/content/doi/10.1108/eb026702/full/html

Human needs that are translated by psychologists into 3 categories:

- physiological needs such as drinking, sleeping, eating

- Emotional / affective needs such as fulfillment, domination

- cognitive needs such as learning a new skill

As surprising as it may seem, these 3 categories are both independent and interconnected. An affective need can lead to a cognitive need (wanting to be more fulfilled in one’s work can lead to training), physiological needs can lead to affective and/or cognitive needs (being healthy leads to better self-esteem and the desire to maintain that self-esteem).

This of course works in the opposite direction, a person who has difficulty fulfilling his or her relationship or social life, for example, will tend to neglect his or her physiological needs or will have stronger emotional needs (recognition, love, loyalty, etc.).

These inteconnections suggest that, in the context of the search for satisfaction of these needs, a person may be led to question how he or she can satisfy them and thus to adopt information-seeking behavior.

Peter Ingwersen is also interested in user behavior and the satisfaction of his needs. (1996: Cognitive Perspectives of Information Retrieval Interactions: Elements of a cognitive IR theory) which, according to him, are divided into 3 categories:

Need for verification: the user wants to verify information or find information with known characteristics. For example, he wants to find precise bibliographic references, an article already read or quoted by another author. He knows that the information exists, and sometimes where he will find it. The precision of the research is then determining.

Conscious need (also called directed need): the user wants to clarify, review or deepen certain aspects of a known subject. The user has information about the subject, such as terms, concepts, images, etc. This is the case of a scientist who is compiling a bibliography or an engineer who wants to exploit a technique.

Unclear need: the user wants to explore new concepts or relationships outside the domains he knows, or the data he knows is vague and incomplete.

Traditional SRIs are not at all adapted to this type of need: the user often does not have, for example, the appropriate vocabulary to formulate his request. Often, they also do not know the sources that could help them. In such circumstances, specifying a search expression is an inappropriate method of modeling the need.

Robert Taylor (1991) distinguishes eight categories of information needs related to information use (cited in Bartlett & Toms, 2005):

- Developing, clarifying a context

- To understand a given situation or problem

- To be knowledgeable about a specific topic

- Verify or confirm another piece of information

- Know what to do and how to do it

- Anticipate events

- Motivate or maintain commitment

- Develop relationships, reputation, status or personal growth.

Besides cognitive needs, there are also pragmatic, psychological or social needs. This typology allows a better understanding of the diversity of situations that motivate the information seeker.

The user’s research skills

Identifying an information need is not natural or innate. One can feel a need without knowing how to characterize it, not knowing what information one needs or not being aware that there is a problem or gap in one’s knowledge (Julien, 1999, cited by Tricot, 2003). We may also be unaware of the dynamic into which the need for information will lead us.

Since the 1990s, we know that it is not enough to know the information need in the form of a search expression to determine the appropriate informational objects to meet it. Other components related to human activity must also be known. The task can be defined as the set of activities that are necessary, habitual or believed to be necessary to achieve a goal.

The notion of context refers to the set of elements that will influence the task (the information retrieval activity), elements that are presented as such

- user context

- context of the information,

- context of the activity

- system context

- context of the user’s environment

- temporal context

- interaction context

These contexts are important because they make it possible to understand how information needs can change within and between situations. To better take into account the context of an informational need, we need to multiply the use of various disciplines: human-human interaction, human-machine interaction or linguistic evolution.

This notion of context introduced by Taylor confirms that when two users type the same search expression on a search engine, the intention is totally different and must therefore lead to a more in-depth reading of the information need not explained in the query.

To conclude on the informational need

As you have seen, search intention is not a fixed and strict need. It is evolving and specific to each individual and context. To conclude this article, I propose a definition in 4 key points of what a search intention is:

1. an awareness of a need for information,

2. a felt need to fill an information gap,

3. a need to resolve uncertainty,

4. a contextualization of the need in relation to situations